Extended Mind Crowdsourcing

Update 13/01/15: the paper containing the research described below is currently available from the HICSS website

This post is one I’m cross-posting both here and on the MobiSoc blog. Here, because it’s my personal translation of one of our latest research papers, and there because it’s a very good paper mostly written and driven by Roger Whitaker, so deserves an ‘official’ blog post!

A lot of use is made of Crowdsourcing in both business and academia. Business likes it because it allows simple tasks to be outsourced for a small cost. Researchers like it because it allows the gathering of large amounts of data from participants, again for minimal cost. (For an example of this, see our TweetCues work (paper here), where we paid Twitter users to take a simple survey and massively increased our sample size for a few dollars). As technology is developing, we can apply crowdsourcing to new problems; particularly those concerned with collective human behaviour and culture.

Crowdsourcing

The traditional definition of crowdsourcing involves several things:

-

a clearly defined crowd

-

a task with a clear goal

-

clear recompense received by the crowd

-

an identified owner of the task

-

an online process

The combination of all these things allows us to complete a large set of simple tasks in a short time and often for a reduced cost. It also provides access to global labour markets for users who may not previously have been able to access these resources.

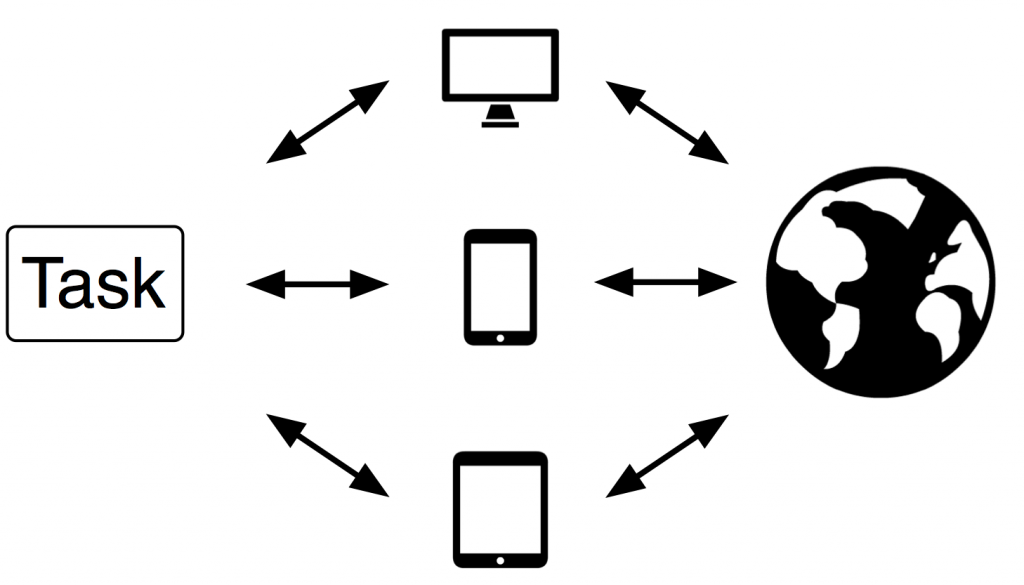

Participatory computing is a related concept to crowdsourcing, based around the idea that the resources and data of computing devices can be shared and used to complete tasks. As with crowdsourcing, these tasks are often large, complex and data-driven, but capable of being broken down into smaller chunks that can be distributed to separate computing devices in order to complete the larger task. BOINC is a clear example of this class of participatory computing.

Extended Mind Crowdsourcing

The extended mind hypothesis describes the way that humans extend their thinking beyond the internal mind, to use external objects. For instance, a person using a notebook to record a memory uses the ‘extended mind’ to record the memory; the internal mind simply recalls that the memory is located in the notebook, an object that is external to the individual.

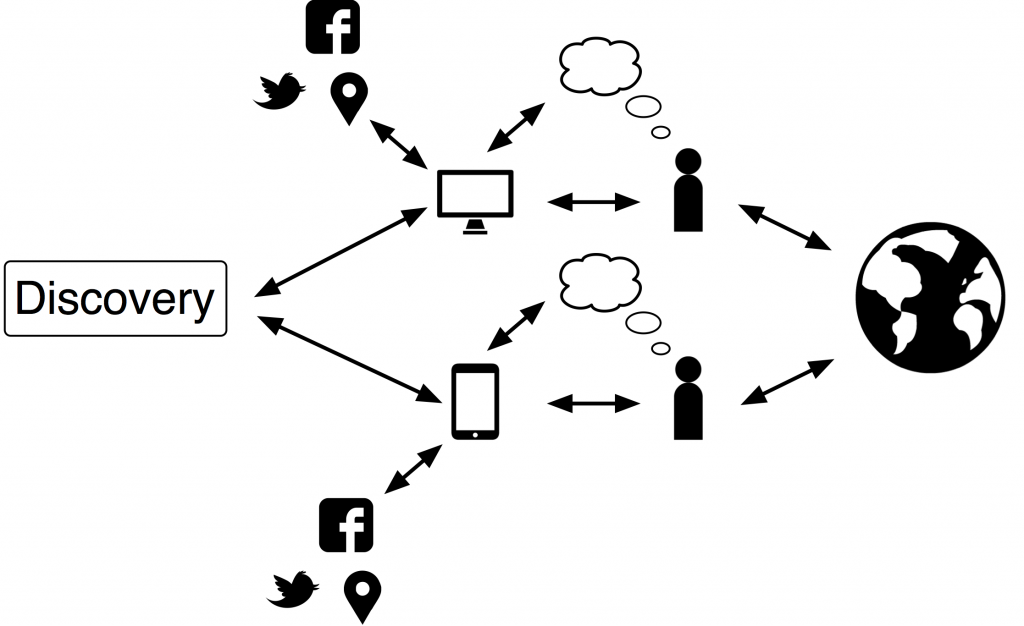

Extended mind crowdsourcing takes crowdsourcing and participatory computing a step further by including the extended mind hypothesis, to allow us to describe systems that use the extended mind of participants, as represented by their devices and objects, in order to add implicit as well as explicit human computation for collective discovery.

What this means is that we can crowdsource the collection of data and completion of tasks using both individual users, their devices, and the extended mind that the two items together represent. Thus by accessing the information stored within a smartphone or similar personal device, and the wider internet services that the device can connect to, we can access the extended mind of a participant and thus learn more about his or her behaviour and individual characteristics. In essence, extended mind crowdsourcing captures the way in which humans undertake and respond to daily activity. In this sense it supports observation of human life and our interpretation of and response to the environment. By including social networks and social media communication within the extended mind, it is clear that while an individual extended mind may represent a single individual human, it is also possible to represent a group, such as a network or a collective using extended mind crowdsourcing.

By combining the ideas of social computing, crowdsourcing, and the extended mind, we are able to access and aggregate the data that is created through our use of technology. This allows us to extend ideas of human cognition into the physical world, in a less formal and structured way than when using other forms of human computational systems. The reduced focus on task driven systems allows EMC to be directed at the solving of loosely defined problems, and those problems where we have no initial expectations of solutions or findings.

This is a new way of thinking about the systems we create in order to solve problems using computational systems focused on humans, but it has the potential to be a powerful tool in our research toolbox. We are presenting this new Extended Mind Crowdsourcing idea this week at HICSS.

Next: CompJ Labs - Postcodes

Previous: Quick and Dirty Twitter API in Python